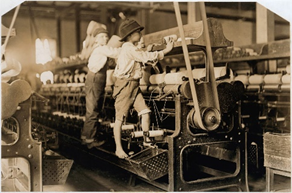

Prompt #2: What was the impact of the Industrial Revolution on the lives of children?

Secondary Source:

Richard Arkwright was one of many factory owners who had child laborers in their factories. Arkwright did not employ people over the age of forty or under the age of six, and 1,254 of his 1,900 workers were children.

“Child Labor Resources,” New Rochelle High School, accessed May 11, 2015, http://nrhs.nred.org/www/nred_nrhs/site/hosting/Resources4SocialStudies/HistSites/ChildLabor/childlaborsupporters.htm.

|

|

|

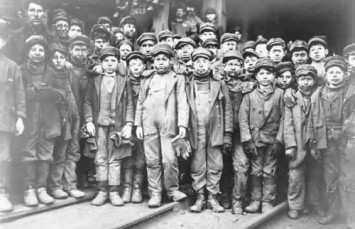

Child Labour workers in Victorian England. Has to deal with video it links to. |

|

http://www.morwellham-quay.co.uk/image/data/cl1.jpg Links to Video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SV3JO_RYIDE |

|

|

|

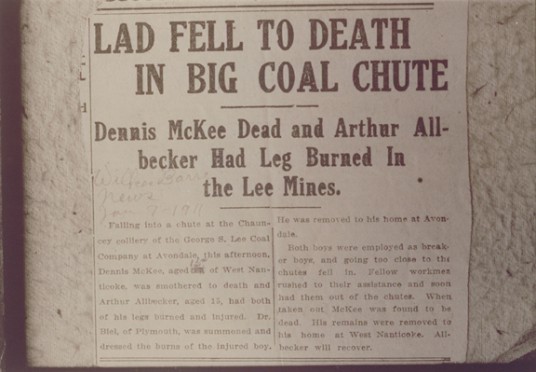

Newspaper article describing the dangers of the coal mines for children. It links to primary source one which deals with anti-child labour. |

|

Lewis W. Hine, “Lad Fell To Death in Big Coal Chute,” Wilkes-Barre News (1911). |

|

|

|

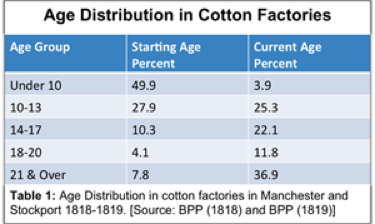

Table showing the age distribution of cotton factory workers in 1818 – 1819 |

|

Wade Thatcher, “Child Labor during the Industrial Revolution,” Ball State University, last revised 2009, http://wathatcher.iweb.bsu.edu/childlabor/files/age1.png. |

Primary Source 1: Sadler Report

Elizabeth Bentley, called in; and Examined.

What age are you?

–Twenty-three.

Where do you live?

–At Leeds.

What time did you begin to work at a factory?

–When I was six years old.

At whose factory did you work?

–Mr. Busk’s.

What kind of mill is it?

–Flax-mill.

What was your business in that mill?

–I was a little doffer.

What were your hours of labour in that mill?

–From 5 in the morning till 9 at night, when they were thronged.

For how long a time together have you worked that excessive length of time?

–For about half a year.

What were your usual hours when you were not so thronged?

–From 6 in the morning till 7 at night.

What time was allowed for your meals?

–Forty minutes at noon.

Had you any time to get your breakfast or drinking?

–No, we got it as we could.

And when your work was bad, you had hardly any time to eat it at all?

–No; we were obliged to leave it or take it home, and when we did not take it, the overlooker took it, and gave it to his pigs.

Do you consider doffing a laborious employment?

–Yes.

Explain what it is you had to do?

–When the frames are full, they have to stop the frames, and take the flyers off, and take the full bobbins off, and carry them to the roller; and then put empty ones on, and set the frame going again.

Does that keep you constantly on your feet?

–Yes, there are so many frames, and they run so quick.

Your labour is very excessive?

–Yes; you have not time for anything.

Suppose you flagged a little, or were too late, what would they do?

–Strap us.

Are they in the habit of strapping those who are last in doffing?

–Yes.

Constantly?

–Yes.

Girls as well as boys?

–Yes.

Have you ever been strapped?

–Yes.

Severely?

–Yes.

Could you eat your food well in that factory?

–No, indeed I had not much to eat, and the little I had I could not eat it, my appetite was so poor, and being covered with dust; and it was no use to take it home, I could not eat it, and the overlooker took it, and gave it to the pigs.

You are speaking of the breakfast?

–Yes.

How far had you to go for dinner?

–We could not go home to dinner.

Where did you dine?

–In the mill.

Did you live far from the mill?

–Yes, two miles.

Had you a clock?

–No, we had not.

Supposing you had not been in time enough in the morning at these mills, what would have been the consequence?

–We should have been quartered.

What do you mean by that?

–If we were a quarter of an hour too late, they would take off half an hour; we only got a penny an hour, and they would take a halfpenny more.

The fine was much more considerable than the loss of time?

–Yes.

Were you also beaten for being too late?

–No, I was never beaten myself, I have seen the boys beaten for being too late.

Were you generally there in time?

–Yes; my mother had been up at 4 o’clock in the morning, and at 2 o’clock in the morning; the colliers used to go to their work about 3 or 4 o’clock, and when she heard them stirring she has got up out of her warm bed, and gone out and asked them the time; and I have sometimes been at Hunslet Car at 2 o’clock in the morning, when it was streaming down with rain, and we have had to stay until the mill was opened.

Primary Source 2:

Archibald Buchanan was interviewed by Robert Peel and his House of Commons Committee on 25th April, 1816.

Question: What is your employment?

Answer: I am employed in the management of cotton-mills in Scotland, the property of James Findlay and Company, merchants in Glasgow. I am also a partner.

Question: How many years have you been employed in the cotton-spinning business?

Answer: About thirty-three years.

Question: What number of persons are employed in the different works?

Answer: I can only speak to the works under my particular management. There are 875 employed at the Catrine works.

Question: How many of those are under ten years of age?

Answer: Twenty-two males and thirty-seven females.

Question: What is the youngest labourer you employ?

Answer: I suppose the youngest may be eight or nine: we have no wish to employ them under ten years of age.

Question: What circumstances have led you to employ any under that age?

Answer: The circumstances, generally the condition of their parents; people with large families, who find great relief from having a child or two put in the factory at an earlier age.

Question: Of the 875 persons, how many are there who cannot read?

Answer: There are eleven males and twenty-six females.

Question: How many who cannot write?

Answer: 660, I think.

Question: What are your hours of work?

Answer: They begin at six o’clock in the morning, they stop at half-past seven at night, and they are allowed half an hour for breakfast and an hour for dinner.

Question: What has been the state of the health of those children that work in your factory?

Answer: Generally very good; much the same as those children in the neighbourhood who are not employed in work.

Question: Suppose the children were taken at six years of age, do you think they would be able to work that number of hours without great indisposition?

Answer: I have seen many instances of children that were taken in even as young as six, whose health did not appear at all to suffer; on the contrary, when they got to maturity, they appeared as healthy, stout, people as any in the country.

Question: Not crippled in their growth?

Answer: No.

Secondary Source:

Summarizing Sources:

- In the Sadler Committee Report, several former child workers were interviewed on the stand in an investigation on the working conditions of workers in textile factories. He finds out that many of the workers had been working under very harsh and cruel conditions, including the threat of beatings for being tardy, having to wake at very early hours and work until very late hours, and an insanely low wage that was further decreased if they were late. Citing this, it can be said that the life of a child in that time was forever changed when the factory owners and overseers were rough with the kids and the children began experiencing deformities that occurred from the position of their bodies when working.

- In the Child Labor Resources on Child Labor Supporters, there is several accounts of factory owners who favored the use of child labor in their factories. The factory owners would not label the child workers as workers, but as “scavengers”. Archibald Buchanan was a cotton mill owner who had 875 child workers in his mills. The youngest of the children he employed would be around eight or nine years old. Also, over six hundred of Buchanan’s’ workers could not write but only thirty seven of them could not read. Archibald felt that the health condition of his workers were, “Generally very good; much the same as those children in the neighbourhood who are not employed in work.” Furthermore, he felt that if he employed children at the age of six, he felt that their health would not suffer either and would appear as any other regular person without any crippling in their growth.

COMPARE & CONTRAST:

- These sources show that many people of the time believed child labor was morally unjust, and the large workloads in the factories had serious consequences upon the children, including deformities and high rates of illiteracy in the children. However, according to the Child Labor Resources there were also people that believed child labor was an excellent idea, and those people were primarily the owners of the factories where the children worked, such as Archibald Buchanan. When the Sadler Report was held years after that interview, the workers interviewed were children a few years around the time of Buchanan’s interview, and they described their horrific experiences in working in the factories at such young ages and the lasting effects of such hard labor at such a developmental time in their life. Buchanan said that he felt as if the health of the children was unaffected by the hard work, however this conflicts with the information that can be found in the Sadler Committee Report, when the workers reported having some lasting deformities in their legs and back from when they worked in the factories owned by men like Buchanan. Additionally, Richard Arkwright, another factory owner, had employed 1,900 people. Two thirds of them were children, approximately 1,250 kids in total all working in treacherous factories, and the youngest children working were around 6 years old.